Modern Times marked the last screen appearance of the Little Tramp - the character which had brought Charles Chaplin world fame, and who still remains the most universally recognised fictional image of a human being in the history of art.

The world from which the Tramp took his farewell was very different from that into which he had been born, two decades earlier, before the First World War. Then he had shared and symbolised the hardships of all the underprivileged of a world only just emerging from the 19th century. Modern Times found him facing very different predicaments in the aftermath of America¹s Great Depression, when mass unemployment coincided with the massive rise of industrial automation.

Chaplin was acutely preoccupied with the social and economic problems of this new age. In 1931 and 1932 he had left Hollywood behind, to embark on an 18-month world tour. In Europe, he had been disturbed to see the rise of nationalism and the social effects of the Depression, of unemployment and of automation. He read books on economic theory; and devised his own Economic Solution, an intelligent exercise in utopian idealism, based on a more equitable distribution not just of wealth but of work. In 1931 he told a newspaper interviewer :

bq. “Unemployment is the vital question … Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy and throw it out of work.”

In Modern Times he set out to transform his observations and anxieties into comedy. The little Tramp - described in the film credits as “a Factory Worker”- is now one of the millions coping with the problems of the 1930s, which are not so very different from anxieties of the 21st century - poverty, unemployment, strikes and strike breakers, political intolerance, economic inequalities, the tyranny of the machine, narcotics. The film’s portentous opening title - “The story of industry, of individual enterprise - humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness” - is followed by a symbolic juxtaposition of shots of sheep being herded and of workers streaming out of a factory. Chaplin’s character is first seen as a worker being driven crazy by his monotonous, inhuman work on a conveyor belt and being used as a guinea pig to test a machine to feed workers as they work.

Paulette GodardExceptionally, the Tramp has a companion in his battle with this new world. On his return to America after a world tour in 1931, Chaplin had met the actress Paulette Goddard, who was to remain, for several years, an ideal partner in his private life. Her personality inspired the character of the “Gamine” in Modern Times - a young girl whose father has been killed in a labour demonstration, and who joins forces with Chaplin. The couple are neither rebels nor victims, but, wrote Chaplin, ”The only two live spirits in a world of automatons. We are children with no sense of responsibility, whereas the rest of humanity is weighed down with duty. We are spiritually free”. In a sense, then, they are anarchists.

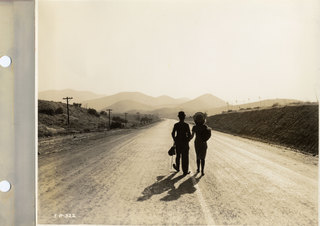

Chaplin at first planned a sadly sentimental ending for the film. While the Tramp was in hospital, recovering from nervous break-down, the Gamine was to become a Nun and so be parted from him for ever. This ending was filmed, but was finally abandoned in favour of a more cheerful finale. “We¹ll get along”, says a title; and the couple, arm in arm, set bravely off down a country lane, towards the horizon

By the time Modern Times was released, talking pictures had been established for almost a decade. Till now, Chaplin had resisted dialogue, knowing that his comedy and its universal understanding depended on silent pantomime. This time though he weakened to the extent of preparing dialogue, and even doing some trial recordings. Finally he thought better of it, and as in City Lights uses only music and sound effects. Human voices are only heard filtered through technological devices - the boss who addresses his workers from a television screen; the salesman who is only a voice on the phonograph.

Just at one moment, though, Chaplin’s own voice is heard directly. Hired as a waiter, the Little Worker is required to stand in for the romantic café tenor. He writes the words on his shirt cuffs, but these fly off with a too-dramatic flourish; and he is obliged to improvise the song in a wonderful, mock-Italian gibberish. Chaplin’s voice had already been heard on radio and in at least one newsreel, but this was the first and only time that the world heard speech from the Little Tramp.

Apart from this indecision over sound and the changed ending, the shooting seems to have been fairly untroubled and, by Chaplin¹s standards, comparatively fast. It may have helped that the essential structure is neatly devised in four “acts” each one more or less equivalent to one of his old two-reel comedies. As the contemporary American critic Otis Ferguson wrote, they might have been individually titled The Shop, The Jailbird, The Watchman and The Singing Waiter.

As he had done for City Lights Chaplin composed his own musical score, giving his arrangers and conductors a harder time than usual, with the result that the distinguished Hollywood musician Alfred Newman walked off the film.

The film became the victim of a strange charge of plagiarism. The Franco-German firm of Tobis claimed that Chaplin had stolen ideas and scenes from another classic film about the 20th century industrial world, A Nous la Liberté, directed by René Clair. The case was weak, and Clair, a great admirer of Chaplin, was deeply embarrassed by it. Yet Tobis persisted, and even renewed its claims in May 1947, after the Second World War. This time the Chaplin Studio finally agreed to a modest payment, just to get rid of the nuisance. Chaplin and his lawyers remained convinced that the determination of the German-dominated company was revenge for the anti-Nazi sentiment of The Great Dictator

Happily for posterity, Tobis failed in their original demand to have Chaplin¹s film permanently suppressed. Instead, Modern Times survives as a commentary on human survival in the industrial, economic and social circumstances of the 20th century society. It remains as relevant, in human terms, for the 21st century.

The Challenge of SoundThe arrival of sound films was a bigger challenge for Chaplin than for any other actor or director. He had won world fame with the universal language of pantomime. If the Little Tramp now began to speak in English he would become incomprehensible to a large part of his international audience. In 1931 he predicted that talking pictures would not last six months, and told an interviewer that ’Dialogue may or may not have a place in comedy … dialogue does not have a place in the sort of comedies I make . .. For myself I know that I cannot use dialogue.’ When the interviewer asked him if he had tried using speech in his films, he retorted “I never tried jumping off the monument in Trafalgar Square, but I have a definite idea that it would be unhealthful… For years I have specialized in one type of comedy - strictly pantomime. I have measured it, gauged it, studied. I have been able to establish exact principles to govern its reactions on audiences. It has a certain pace and tempo. Dialogue, to my way of thinking, always slows action, because action must wait upon words.”

By the time he came to prepare Modern Times however, it seemed that he had steeled himself to use speech. In the Chaplin archives there is a dialogue script for all scenes in Modern Times up to and including the department store sequence. The dialogue which Chaplin planned for his own character is staccato, quippy, touched with nonsense. He began to rehearse the dialogue for the scenes in the jail and warden’s office; but after only a day or so seems to have been deeply dissatisfied with the results. No more dialogue scenes were to be shot for Modern Times

Chaplin did proceed with sound effects, however, and took a personal interest in the technique of their creation. For a scene involving rumbling stomachs, he created the noises himself by blowing bubbles into a pail of water. The fact that Chaplin was sufficiently keen to create the effects himself in this way suggests the extent to which he was intrigued by sound problems at this time. A memorandum about possible musical effects notes: ’Natural sounds part of composition, i.e. Auto horns, sirens, and cowbells worked into the music.’ The sound effects, as the Dardennes brothers point out in the accompanying commentary, became an element of the musical score.

The PremieresModern Times was launched more quietly than previous Chaplin films. The film opened in New York on 5 February 1936, and in London on 11 February. Chaplin and his co-star Paulette Goddard attended a third and the most glamorous “premiére” in Hollywood on 12 February. The venue was Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, which had opened in 1927 as “a shrine to art … the crowning achievement of a brilliant career … the realization of the vision of a simple soul, a master showman … Sid Grauman”. The guests were handed programmes designed in lush and glamorous Art Deco style, printed in black and red on gold paper.

In the past Grauman had devised elaborate live stage shows for Chaplin premieres, but this time the entertainment was entirely on screen, with a newsreel, a travelogue, a Technicolor interest film, and the latest issue of the current documentary series The March of Time - though, emphasising its topicality, this was announced as “Subject to weather conditions for Air Express”.

The most notable item in the supporting programme was a new Silly Symphony from the Walt Disney Studios, Mickey’s Orphan Concert. The inclusion of this cartoon exemplified an intense mutual admiration between Chaplin and Disney, who both recognised similarities in the other’s work. Disney bought advertising space in the programme, “In appreciation of the pantomimist supreme whose inimitable artistry and craftsmanship are timeless”. It was signed, “Mickey Mouse and Walt Disney”.